Toycoin Part 3b: Transactions Revised

Note: the toycoin series of posts is for learning / illustrative purposes only; no part of it should be considered secure or useful for real-world purposes.

At the end of the previous post, there were a number of questions about how transactions would actually work. My confusion stemmed from (among other things) a lack of consideration for how ownership state is handled by the blockchain. In simpler terms: how do we know who owns how much coin?

With traditional wallets (the kind we carry around, or digital wallets like bank accounts), we have a number that represents the amount of money we have in the account. The number goes up or down as we receive or send money. This works for physical wallets because we can obviously count how much money there is (or is not!), assuming away the problem of counterfeit currency. And for digital wallets, we trust the centralized, regulated, mostly insured banking system to safeguard the validity of each transaction and the value of our accounts.

Questions arise, though, when applying the same mental model to the previous definition of transactions.

A transaction is value received from another wallet, with a digital trail of signatures to prove prior ownership:

class Transaction(TypedDict):

receiver: Address

amount: float

signature: signature.Signature

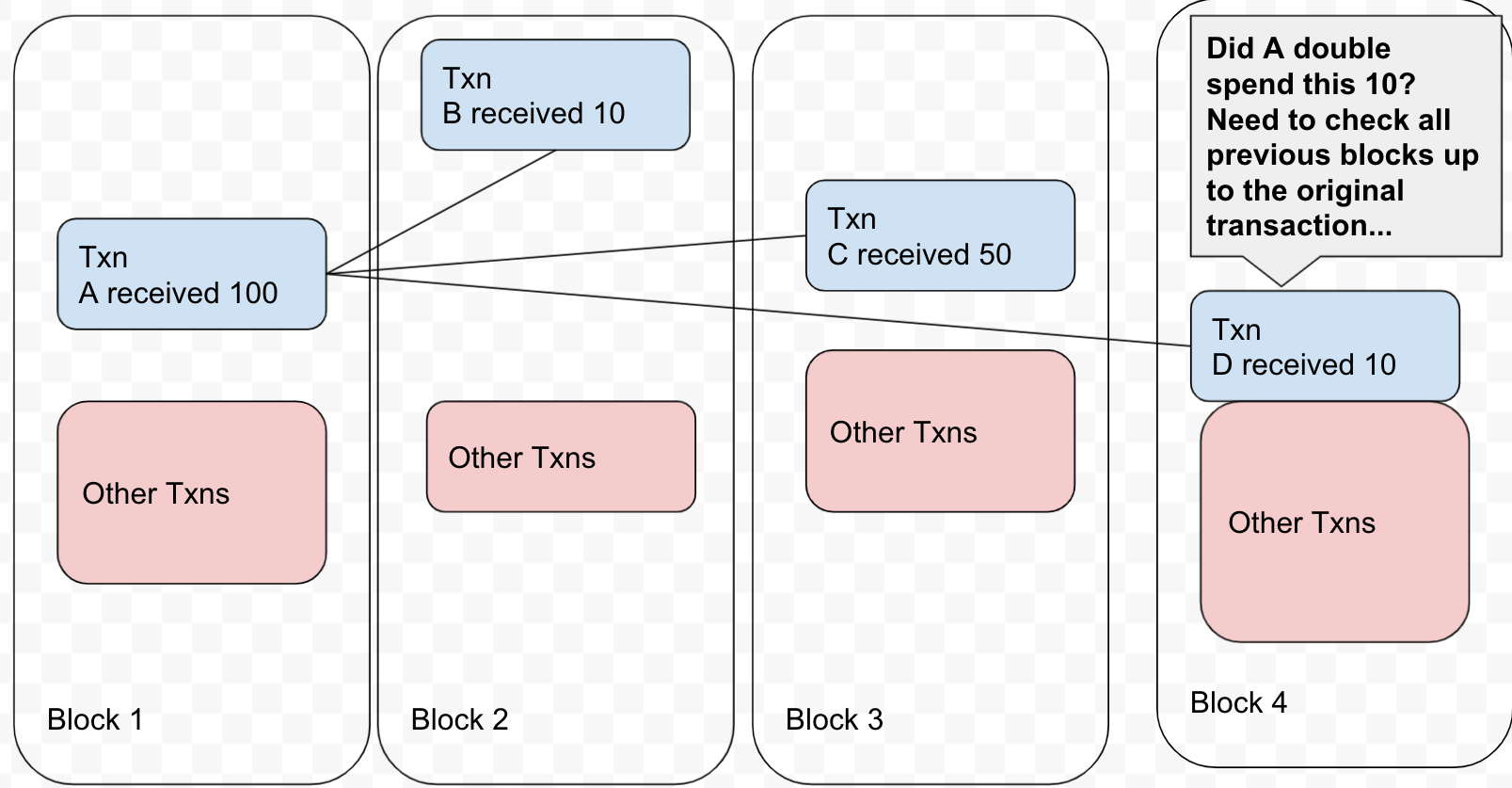

What if the receiver then wants to split the amount into multiple payees? This seems especially problematic if the split occurs over time. The verification of a peyment would then be dependent on an arbitrary number of prior transactions at arbitrary times in the past (to ensure there has been no double-spending). Tracking that state on the blockchain is inefficient and a correct implementation could be tricky.

Section 9 “Combining and Splitting Value” of the Bitcoin paper reveals that the conceptual basis for transactions is much simpler – each transaction is for a single unit of coin:

Although it would be possible to handle coins individually, it would be unwieldy to make a

separate transaction for every cent in a transfer. To allow value to be split and combined,

transactions contain multiple inputs and outputs. Normally there will be either a single input

from a larger previous transaction or multiple inputs combining smaller amounts, and at most two

outputs: one for the payment, and one returning the change, if any, back to the sender.

Revising Transactions

We can revise transactions so that their value is always spent – either sent entirely to the recipient (one output), or sent partially and the remainder coming back as change (two outputs).

class Transaction(TypedDict):

previous_hashes: List[hash.Hash]

receiver: Address

receiver_value: int

receiver_signature: signature.Signature

sender: Address

sender_change: int

sender_signature: signature.Signature

class Token(TypedDict):

txn_hash: hash.Hash

owner: Address

value: int

signature: signature.Signature

Note that:

previous_hashesis included to make it more convenient to verify the transaction signatures- units are now ints instead of floats (for simplicity and precision)

- seperate signatures are required for the value sent and the change received

Tokenis just a subset of theTransactionobject; it’s not necessary but simplfies some processing logic

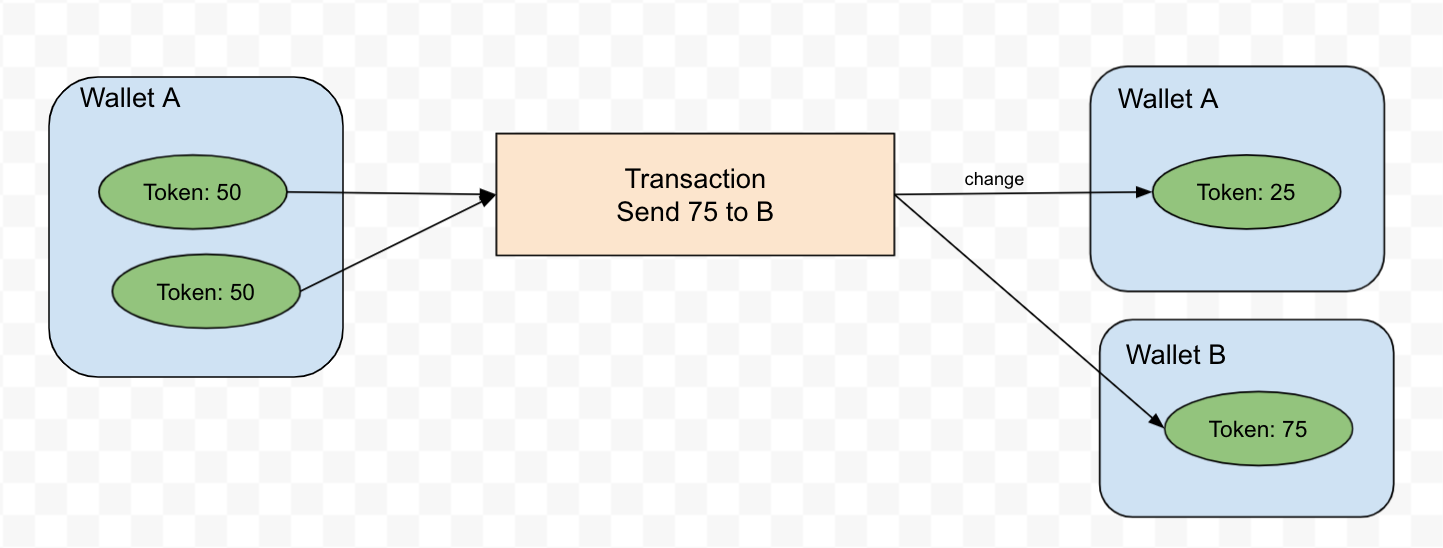

Imagining that client wallet applications hold tokens, a transaction looks like this at a high level:

Each token is unique and immutable (just like transactions are), so the change that A receives is in the form of an entirely new token.

Revising the send logic accordingly:

def send(receiver_pub: bytes,

sender_priv: rsa.RSAPrivateKey,

send_value: int,

tokens: List[Token]

) -> Optional[Tuple[List[Token], Transaction]]:

"""Generate a send transaction.

Returns None if token value is insufficient, and provides change if

token value is greater than the send value.

"""

sum_value = sum_tokens(tokens)

if sum_value < send_value:

return None

hs = [token['txn_hash'] for token in tokens]

txn : Transaction

txn = {'previous_hashes': hs,

'receiver': receiver_pub,

'receiver_value': send_value,

'receiver_signature': signature.sign(sender_priv,

b''.join(hs) + receiver_pub),

'sender': sender_pub,

'sender_change': sum_value - send_value,

'sender_signature': signature.sign(sender_priv,

b''.join(hs) + sender_pub)

}

return (tokens, txn)

The idea is that client wallet applications will call this send function and broadcast the output to blockchain nodes for processing. The output includes the tokens consumed in the transaction to facilitate validation of the transaction.

def valid_txn(tokens: List[Token], txn: Transaction) -> bool:

"""Validate transaction signatures."""

owners = [token['owner'] for token in tokens]

if not owners or len(set(owners)) > 1:

return False

owner = owners[0]

hs = b''.join(txn['previous_hashes'])

v1 = signature.verify(txn['receiver_signature'],

signature.load_pub_key_bytes(owner),

hs + txn['receiver'])

v2 = signature.verify(txn['sender_signature'],

signature.load_pub_key_bytes(owner),

hs + txn['sender'])

return v1 and v2

Testing

It’s much easier to test with wallets to hold tokens, so tests will be covered in the next post.

Wrapping Up

It took me a while to grok that there isn’t a centralized authority that tracks the state of the network (i.e. who is holding how much coin) – evne though that’s the key feature of blockchains!

The revised transaction data model feels right (or at least, more right) and better aligned with the Nakamoto paper.

So far everything consists of pure functions (i.e. not dealing with state or IO, like the networking aspects). It probably makes sense to keep everything pure for as long as possible, leaving the stateful network implementation for last.